The U.S. government this week formally ended the COVID-19 public health emergency period after more than three years.

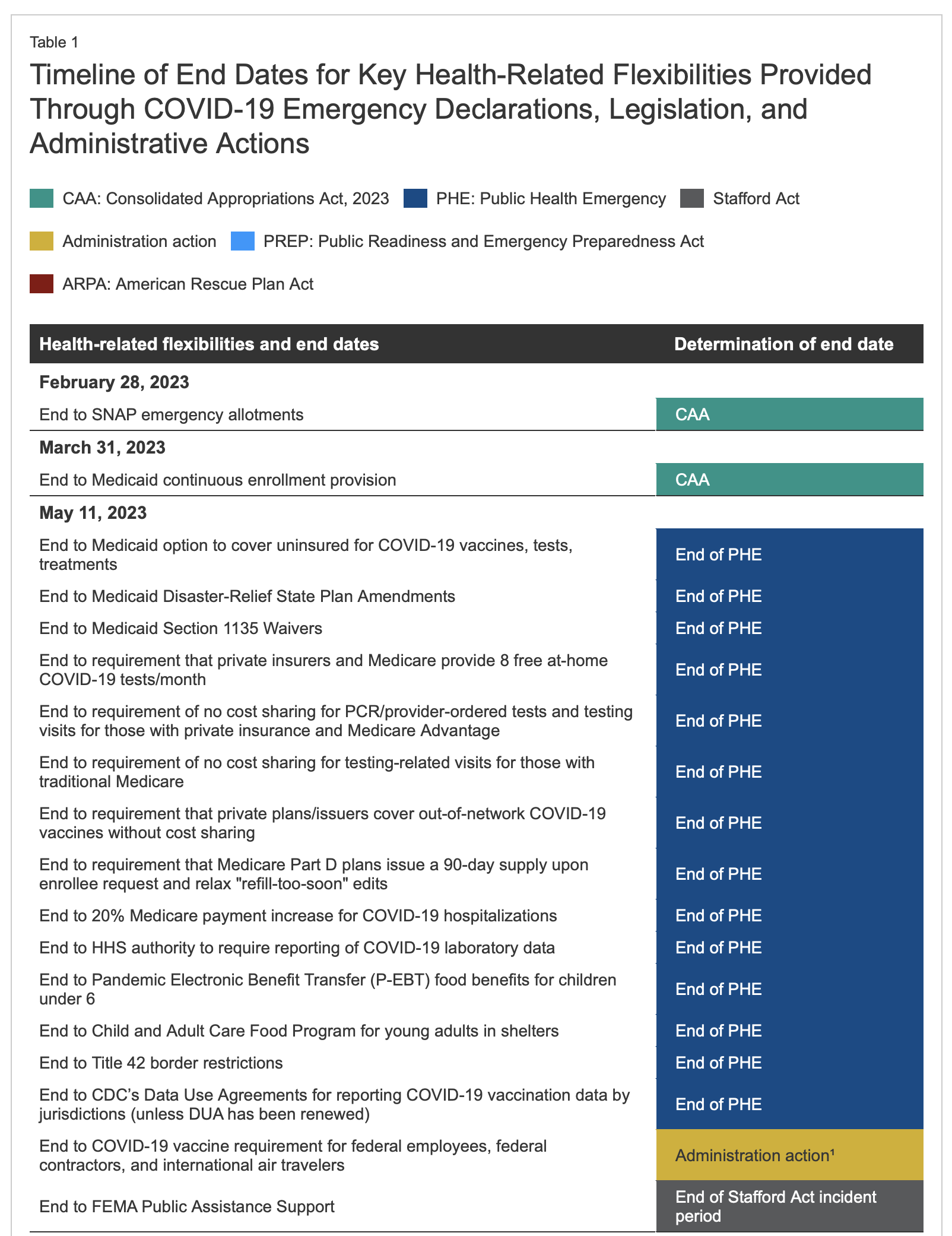

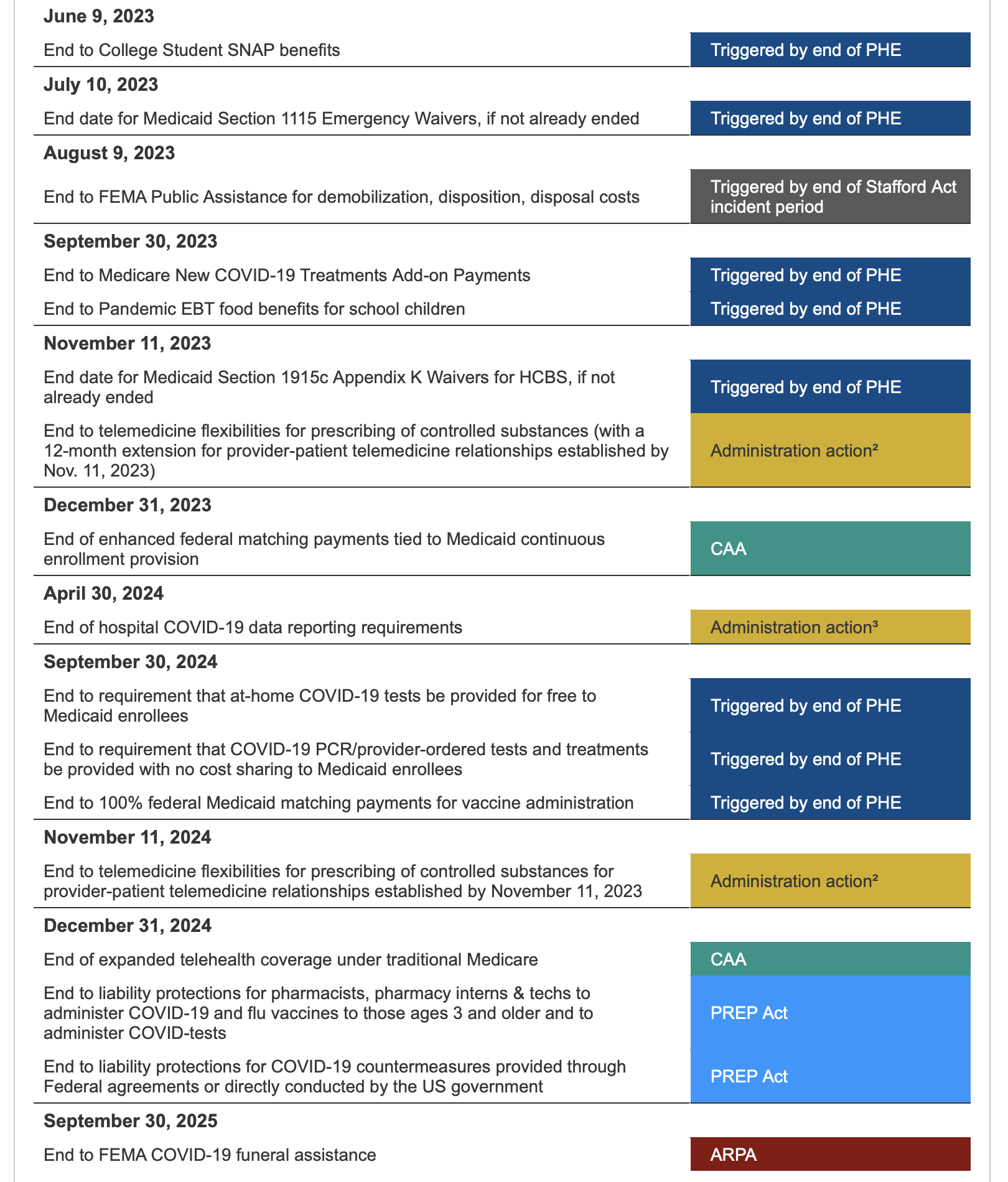

The move brings many procedural changes to the operations of the U.S. government, mostly involving special authorities granted to various agencies to handle elements of the pandemic. A list of changes can be found below:

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar on January 31, 2020 declared the public health emergency.

The end of the public health emergency comes alongside the end of the COVID-19 National Emergency, which was first declared by then-President Trump on March 13, 2020.

The Senate in late March 2023 voted to end the national emergency and President Biden signed the measure after publicly stating that he “strongly opposed” the resolution. The bill passed the House in January by a 220-210 vote and the Senate 68-23.

President Biden extended both emergencies multiple times since January 2021. Both of those have now come to a formal end on May 11, 2023, over three years after they begun.

“An abrupt end to the emergency declarations would create wide-ranging chaos and uncertainty throughout the healthcare system – for states, for hospitals and doctors’ offices and, most importantly, for tens of millions of Americans,” the White House Office of Management and Budget said in a Statement of Administrative Policy, despite President Biden’s decision to formally end both emergency periods.

In recent months, President Biden had requested of Congress billions of dollars to extend free COVID-19 vaccines and testing, but Congress refused to provide the funding.

The end to the public health emergency also ends the Department of Homeland Security’s “Title 42” policy, which is emergency authority DHS can use to refuse U.S. entry to migrants on the grounds of preventing the spread of infectious diseases. The policy grants DHS the right under certain emergency conditions to refuse entry and the right to seek asylum on the grounds of public health.